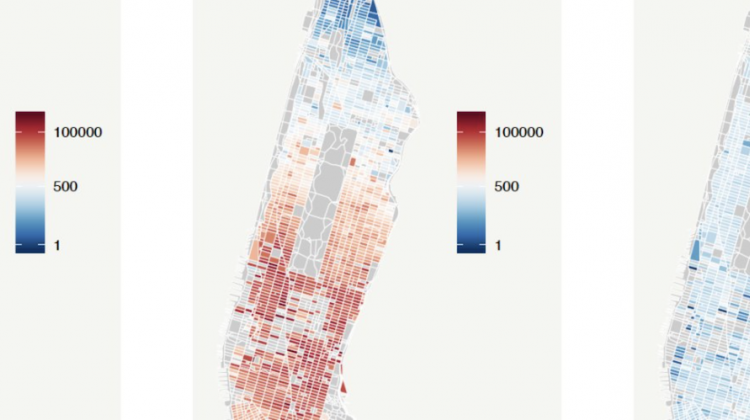

We live in consumer cities, where the scale of the city provides households with a diversity of retail and other amenities. For a household in a given neighborhood, access to these amenities depends on two features: its transportation links to other neighborhoods, and the scale of amenities in those neighborhoods. Car-based networks (such as in Phoenix) necessitate parking at origin and destination in order to establish a link — but the space devoted to parking lowers its capacity in terms of housing and amenities. Walking and transit networks (as in Manhattan) have no such trade-off, and a city reliant on them will be able to make fuller use of its land for productive purposes like amenities and housing. However, they hinder mobility in other ways: walking does not get you far, and using transit requires adhering to the routes and stops the city’s transit agency provides. In this paper, we develop and calibrate a spatial consumer city model to study what would happen if Phoenix banned cars, delineating the roles of parking conversion, of the light rail network, and of a last mile option. We show that the space required by automobile parking limits the ability of a car-based city to provide a high quality of life. At the same time, Phoenix’s current light rail line would not provide sufficient accessibility to sustain that quality of life without cars, even accounting for better use of parking. However, the addition of a last-mile option in tandem with parking conversion would be able to sustain a higher level of vibrancy than either option alone. We then investigate the reverse case: what would happen if Manhattan required parking? Using our calibrated model, we show that the island would essentially empty, as the declining capacity of each block lowers the vibrancy of the city, inducing still more residents to leave. Altogether, these model outcomes tell a story of agglomeration through complementarities: the transportation network and incumbent land use must ensure a high degree of access to jobs and amenities in order for a sufficient scale of households to locate in a city and thereby support those amenities.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3655799