A Mass Grave, and a Poignant Window into Boston’s Past

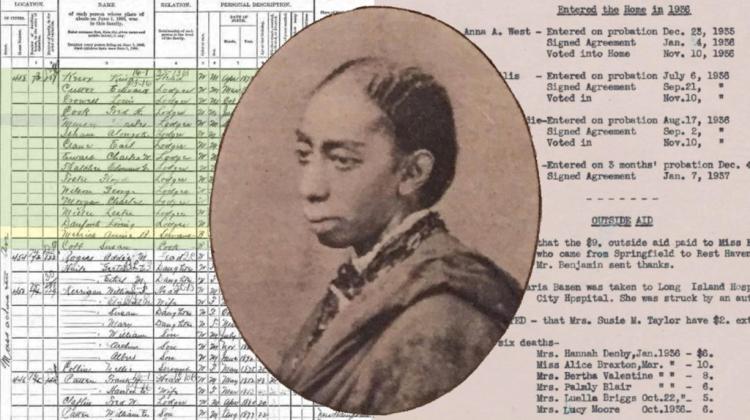

1900 Census showing residents of the Home for Aged Colored Women in green, including Annie Merrick (in yellow), who was born into enslavement in North Carolina in 1848. Center: Eliza Gardner was a religious leader and community activist who died at the home on Jan. 4, 1922, at age 90. Right: Administrative records from Jan. 12, 1937.

Written by Karilyn Crockett, assistant professor of urban history, public policy, and planning at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and former chief of equity for the city of Boston. Published in the Boston Globe February 3, 2025.

In Dorchester’s Cedar Grove Cemetery, two flat stone slabs feature a simple inscription: “Home for Aged Colored Women.” The markers, which barely rise above the ground, offer no names, no explanation.

What lies beneath these markers — and what’s the history behind them?

That’s what Joyce Linehan, former chief of policy and planning for mayor Martin J. Walsh and a Dorchester native, wondered when she encountered the stones during walks in the cemetery in 2021.

Those questions have sparked a citywide research quest, creating an unprecedented opportunity to rediscover a vital part of Boston’s history and imagine a new memorial for more than 130 Black women who attended to the city’s many needs.

I was one of the women Linehan called to discuss her discovery. And I wondered: What good is a marker if we don’t know anything about the lives it was made to remember?

I did what any curious but busy college professor might do: I assigned the project to students. In 2022, students in my “(Un)Dead Geographies” planning history seminar at Massachusetts Institute of Technology dove in to find out as much as they could about the Home for Aged Colored Women and its residents.

Uncovering the stories of these women, many of whom worked for decades as domestic servants for wealthy Boston families, has been a revelation. Using US Census records, Ancestry.com, and materials from the Massachusetts Historical Society and National Park Service, students painstakingly sifted through newspapers, birth certificates, and cursive-laden archival records to bring these women to life.

The Home for Aged Colored Women was founded in 1860 by a group of well-connected Boston leaders, including Rebecca Parker Clarke, the mother of a prominent white Unitarian minister, and Leonard A. Grimes, the erudite pastor of Twelfth Baptist Church. They established a home in downtown Boston to provide housing and aid for older Black women with limited means.

About a decade prior, another haven — the Home for Aged Women — had been created for native-born, Protestant white women. The message there was clear: Black women, immigrant women, and Irish Catholic women need not apply.

For decades until it closed in 1944, the Home for Aged Colored Women provided housing to hundreds, funded by an interracial roster of donors. For other women, it offered aid ranging from $2 to $12 per month.

Some of the early residents were previously enslaved, while others were born free. Most had worked and had been insufficiently compensated or recognized for their many contributions to the city’s life and its residents.

Take Charlotte Cougle: She was born into slavery in Liberty County, Ga. When she was around 53, her enslaver, a state senator named Jacob Wood, sent her to Boston to accompany his 7-year-old granddaughter, Sarah Frances T. Pierce, while she attended boarding school.

After Wood died, in accordance with his will, the 150 enslaved people on his plantation were emancipated. They were sent to Liberia. Cougle’s own daughter was among them, and there is no evidence she and her mother ever reunited. When Wood’s granddaughter finished school and planned to marry, she invited Cougle to return to Georgia and live at her husband’s home as an enslaved woman. Cougle refused. She had vowed to Wood that she would never return to the South.

Cougle stayed in Boston at the home of the woman who had run the boarding school until 1860, when she joined the first group to move into the Home for Aged ColoredWomen. She lived her final years there before being laid to rest at Cedar Grove Cemetery in 1878, at the age of 90.

Rebecca Barbadoes had a very different story. Barbadoes, born in 1833, descended from a longtime Massachusetts family rooted in politics and entrepreneurship. “Her grandfather was a resident of Lexington and an ancestor fought in the Revolutionary Army,” according to a brief history of the home by Esther MacCarthy. Barbadoes’s father, James G. Barbadoes, was a passionate antislavery activist known for his advocacy for land rights for Black Americans. Several family members were tailors, clothing dealers, and dressmakers who honed their trades in Boston’s West End.

Rebecca Barbadoes also had an enterprising streak and worked as an attendant on the Boston and Bangor Boat, a marvel of 19th-century steam technology. In this role, she would have been well-versed in the tourist and merchant activities of the North Atlantic coastline. She received aid from the home for a few years and then became a resident in 1916. She was buried in 1921.

Popular accounts of Boston’s mid-19th-century story often highlight the scrappy rise of Irish workers and their families or an occasional Underground Railroad or fugitive slave victory. But few stories of this period chronicle Black women’s everyday lives. Research on the Home for Aged Colored Women and its beneficiaries offers an important opportunity to make a much-needed historical correction.

A new public memorial to honor these women and their sacrifices for and contributions to Boston is also overdue. Multiple groups are now collaborating to make that happen, including the Friends of Cedar Grove Cemetery and Boston Women’s Heritage Trail. Last year the Legacy Fund for Boston, a public charity that funds historic-preservation projects, provided a $50,000 grant to support a community-based process to create that memorial. Whatever form it takes — and I hope it ultimately includes a larger collective research project and online site where anyone who wants to learn or contribute can do so — the lives of 133 women buried at Cedar Grove Cemetery offer a poignant window into a past we only thought we knew.