Manifestations of Structural Poverty

How do changes in built environments of twentieth century American cities reflect the social and geographic politics of a city? What can we gain and how can we improve our planning efforts by altering our way of seeing - with the explicit intention to recognize multiple layers of invisible structures that script our physical surroundings?

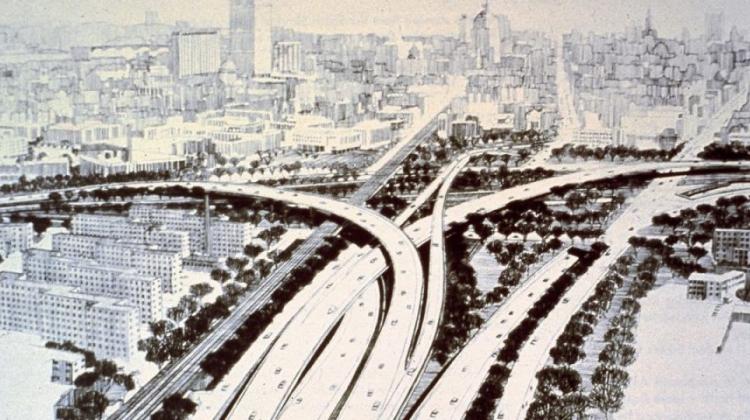

Karilyn Crockett, previously a Mel King Scholar and the new Lecturer of Public Policy and Urban Planning, is working to answer these questions by blending archival research, ethnographic fieldwork, and personal connections within communities. In the interlude between her times at DUSP, Crockett served as Director of Economic Policy and Research and Director of Small Business Development for the City of Boston. In her academic and professional capacities, she highlights how invisible, social and power structures manipulate, inform, and manifest in the built environment we navigate on a daily basis. Crockett’s new book, People before Highways: Boston Activists, Urban Planners, and a New Movement for City Making (University of Massachusetts Press, 2018), applies this framework for exploring a city in the context of the 1950s and 1960s planning attempting to build multiple highways surrounding and dividing the city of Boston - plans which would have disproportionately impacted poor neighborhoods and communities of color. Crockett explores how social capital, built during the civil rights and antiwar movements, contributed to the emergence of unlikely coalitions of activists, capable of organizing and resisting these development plans.

What drew you to focus on highways as a model of social movements interacting and influencing a renewal of urban planning?

Karilyn: As I kid, I remember riding on the back of a bike and seeing all these empty parcels between my grandmother’s apartment and my uncle’s house in Roxbury. I must have been 7 or 8 years old. I thought it looked cool but spooky at the same time. I had no idea that this dusty area had been cleared for an interstate highway and that my deep fascination with changing land patterns and neighborhoods was officially getting launched.

As soon as I graduated college, I started a non-profit organization that hired high school students to research their family and local histories, turning those stories into youth-led walking tours, marketed and sold directly to public audiences. This professional experience was transformative to my understanding of how social movements are sparked and how meaningful, long-term urban change is sustained among populations with limited economic resources. My graduate work and service in the Mayor’s Office of Economic Development further solidified my practice and intellectual commitment to expanding how practitioners, students, advocates and researchers understand public policy as a useful tool for creating just and racially inclusive cities.

Would you speak more to viewing a city as the physical manifestation of social history and power dynamics, specifically how that lens might help individuals promote equity and justice?

Karilyn: I believe every person represents an embodied archive of memories, data and experiences that coalesce into unique, internal geographies and tiny maps. And how we interact with one another as well as the places where we dwell is fully shaped by these types of internal mappings. For example, when I look at a city map, I want to know who lives where - but I also want to know who does not go where, and whether this has changed over time.

I think truly revelatory social histories probe our understanding of individual stories while also illuminating particular population patterns. The history of built forms and urbanization is a backdrop for social narratives. Efforts to articulate equity and justice agendas are not new. Advocates, activists, and allies working to further equity in both the social and physical urban form are well served by intentionally re-connecting their efforts to longer historical timelines - and the authors of those timelines - inside and especially outside of the academy.

How is this contextualized, layered perspective of a city informing your class and your research at DUSP?

Karilyn: It’s amazing to have an opportunity to reflect upon cities with DUSP’s powerful cohort of urban analysts, advocates, observers and scholars. My current research examines how place-based urban resistance campaigns as well as the creation and codification of collective memory works to drive new frameworks for city planning and local policy-making. I am continuously tracking the depth and range of progressive urban plans that bubbled out of the Boston anti-highway movement. Here an unlikely multi-racial, regional coalition came together, stopped a billion-dollar interstate highway project and, with a newly persuaded governor, advanced the 1973 federal-aid highway act which established national policy and funding access for U.S. public transportation.

This semester, I am teaching 11.401, Introduction to Housing, Community and Economic Development. My course focuses on the shape and determinants of political, social, and economic inequality in urban America. What is the impact to student’s perception of planning as a field when we explore the way we use cities to imagine and project urban utopias? How do we define justice and how does our model and metric of justice balance with urban policies? I frame the classroom experience as an intellectual mid-way point between home and work identities - offering students and faculty a space to challenge presumptions expand their way of seeing – opening pathways for chasing new projects and ideas, rooted in a deeper understanding of place, history, and social narratives.