Expanding Access Across a City

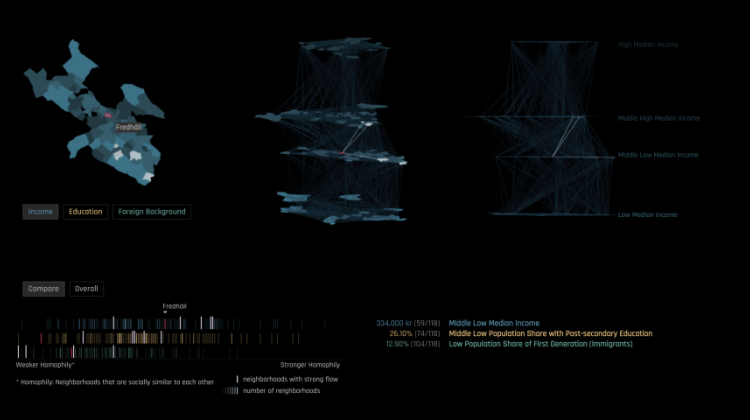

In cities, how many individuals feel connected with fellow citizens even across socioeconomic and spatial differences? To answer this question, researchers at MIT's Senseable City Lab analyzed the “linkage strength” between parts of Stockholm, Sweden, using geotagged Twitter and census data to measure how people from different neighborhoods move around the city. They examined this data to determine if socioeconomic differences such as income, education, and immigration history between two areas affects whether people move between them. Their findings have been published in a recent paper in Plos One.

"People are drawn to opportunities that cities create. As residents move through a city, from work to the grocery store to picking the kids up from school, they disseminate ideas and resources. Over time, the circulation of people throughout a city creates more opportunities, attracting more people, in a virtuous cycle that leads to rapid growth of social products like income and innovation with city size," said Paolo Santi, Principle Research Scientist at Senseable City Lab. " However, a growing body of literature suggests that the circulation of people through cities are in fact quite irregular. To unveil these irregularities, past research has been based on static information, such as residential segregation, or reduced mobility samples from surveys and personal accounts. Many important questions related to how socio-economic status influences the way we move and interact in cities have so far mostly been investigated through small-scale surveys and focus interviews. Our paper shows that social media datasets can be an additional toolset to address these questions at a larger scale.”

In their paper, Analysis of mobility homophily in Stockholm, the research team used geotagged Twitter data to understand how people move around the city and which places they visit in their daily trips. Their aim was to understand whether people move only through parts of Stockholm that share similar socioeconomic characteristics, creating enclaves within cities, or whether they move through diverse collections of neighborhoods, connecting far parts of the city to one another. Lead author, Cate Heine, said, “It’s natural to expect that people are likely to travel through neighborhoods that are similar to one another. Our research allows us to quantify this tendency and identify exactly what kinds of neighborhoods are connected to one another by the flow of people---are people likely to move through neighborhoods that are physically close together? That are socioeconomically similar? That shares certain amenities?”

The analysis required two datasets: 300 thousand geotagged tweets over a period of over three years to describe movement of people between neighborhoods in Stockholm, and census data to describe the socioeconomic dissimilarity between 132 neighborhoods (or 'stadsdelar') of the city—each containing an average of 6,000 residents.

The research indicates some level of homophily in the way that individuals choose to move throughout a city: differences in educational level and income have significant, negative effect on the linkage strength between two regions, indicating that socioeconomically different neighborhoods are less likely to be connected to one another. Driving and transit time are also significant predictors of linkage strength and have an even larger effect than socioeconomic differences. The longer it takes to get to a place, the weaker the linkage strength. Cross-pollination of ideas and people across cities are key for human development, but as the research suggests, people often tend to move within select bubbles.

The research team included: Cate Heine, Cristina Marquez, Paolo Santi, Marcus Sundberg, Miriam Nordfors, and Senseable City Lab Director, Carlo Ratti.

The Senseable City Lab, founded in 2005, is a multidisciplinary research group that studies the interface between cities, people, and technologies. It investigates how the ubiquity of digital devices and the various telecommunication networks that augment our cities are impacting urban living. With an overall goal of anticipating future trends, the Lab brings together researchers from many academic disciplines to work on groundbreaking ideas and innovate real-world demonstrations. This research is undertaken in partnership with cities, the private sector and other universities; through this collaborative approach we strive to reveal how a new, rapidly expanding network of digital devices is serving to modify the traditional principles of understanding, describing and inhabiting cities.

“By using Big Data, we can create plans with urban developers to integrate cities, which can enhance all neighborhoods, allowing many more to thrive and disseminate knowledge,” said Ratti.